Who Is The Final Judge or Interpreter in Constitutional Controversies:

Who Is The Final Judge or Interpreter in Constitutional Controversies:

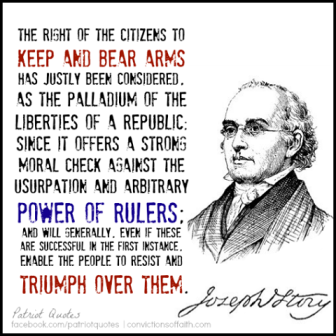

JOSEPH STORY was born on September 18, 1779, in Marblehead, Massachusetts. He graduated from Harvard College in 1798. Story read law in the offices of two Marblehead attorneys and was admitted to the bar in 1801. He established a law practice in Salem, Massachusetts. In 1805, Story served one term in the Massachusetts Legislature, and in 1808 he was elected to the United States House of Representatives. After one term, he returned to the Massachusetts Lower House, and in 1811 he was elected Speaker. On November 18, 1811, President James Madison nominated Story to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment on February 3, 1812. At the age of thirty-two, Story was the youngest person ever appointed to the Supreme Court. While on the Supreme Court, Story served as a delegate to the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention of 1820 and was a Professor of Law at Harvard, where he wrote a series of nine commentaries on the law, each of which was published in several editions. Story served on the Supreme Court for thirty-three years. He died on September 10, 1845, at the age of sixty-five.

§ 373. THE consideration of the question, whether the constitution has made provision for any common arbiter to construe its powers and obligations, would properly find a place in the analysis of the different clauses of that instrument. But, as it is immediately connected with the subject before us, it seems expedient in this place to give it a deliberate attention.1

§ 374. In order to clear the question of all minor points, which might embarrass us in the discussion, it is necessary to suggest a few preliminary remarks. The constitution, contemplating the grant of limited powers, and distributing them among various functionaries, and the state governments, and their functionaries, being also clothed with limited powers, subordinate to those granted to the general government, whenever any question arises, as to the exercise of any power by any of these functionaries under the state, or federal government, it is of necessity, that such functionaries must, in the first instance, decide upon the constitutionality of the exercise of such power.2 It may arise in the course of the discharge of the functions of any one, or of all, of the great departments of government, the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. The officers of each of these departments are equally bound by their oaths of office to support the constitution of the United States, and are therefore conscientiously bound to abstain from all acts, which are inconsistent with it. Whenever, therefore, they are required to act in a case, not hitherto settled by any proper authority, these functionaries must, in the first instance, decide, each for himself, whether, consistently with the constitution, the act can be done. If, for instance, the president is required to do any act, he is not only authorized, but required, to decide for himself, whether, consistently with his constitutional duties, he can do the act.3 So, if a proposition be before congress, every member of the legislative body is bound to examine, and decide for himself, whether the bill or resolution is within the constitutional reach of the legislative powers confided to congress. And in many cases the decisions of the executive and legislative departments, thus made, become final and conclusive, being from their very nature and character incapable of revision. Thus, in measures exclusively of a political, legislative, or executive character, it is plain, that as the supreme authority, as to these questions, belongs to the legislative and executive departments, they cannot be re-examined elsewhere. Thus, congress having the power to declare war, to levy taxes, to appropriate money, to regulate intercourse and commerce with foreign nations, their mode of executing these powers can never become the subject of reexamination in any other tribunal. So the power to make treaties being confided to the president and senate, when a treaty is properly ratified, it becomes the law of the land, and no other tribunal can gainsay its stipulations. Yet cases may readily be imagined, in which a tax may be laid, or a treaty made, upon motives and grounds wholly beside the intention of the constitution.4 The remedy, however, in such cases is solely by an appeal to the people at the elections; or by the salutary power of amendment, provided by the constitution itself.5

§ 375. But, where the question is of a different nature, and capable of judicial inquiry and decision, there it admits of a very different consideration. The decision then made, whether in favour, or against the constitutionality of the act, by the state, or by the national authority, by the legislature, or by the executive, being capable, in its own nature, of being brought to the test of the constitution, is subject to judicial revision. It is in such cases, as we conceive, that there is a final and common arbiter provided by the constitution itself, to whose decisions all others are subordinate; and that arbiter is the supreme judicial authority of the courts of the Union.6

§ 376. Let us examine the grounds, on which this doctrine is maintained. The constitution declares, (Art. 6,) that “This constitution, and the laws of the United States, which shall be made in pursuance thereof, and all treaties, etc. shall be the supreme law of the land.” It also declares, (Art. 3,) that “The judicial power shall extend to all cases in law and equity, arising under this constitution, the laws of the United States and treaties made, and which shall be made under their authority.” It further declares, ( Art. 3,) that the judicial power of the United States “shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts, as the congress may, from time to time, ordain and establish.” Here, then, we have express, and determinate provisions upon the very subject. Nothing is imperfect, and nothing is left to implication. The constitution is the supreme law; the judicial power extends to all cases arising in law and equity under it; and the courts of the United States are, and, in the last resort, the Supreme Court of the United States is, to be vested with this judicial power. No man can doubt or deny, that the power to construe the constitution is a judicial power.7 The power to construe a treaty is clearly so, when the case arises in judgment in a controversy between individuals.8 The like principle must apply, where the meaning of the constitution arises in a judicial controversy; for it is an appropriate function of the judiciary to construe laws.9 If, then, a case under the constitution does arise, if it is capable of judicial examination and decision, we see, that the very tribunal is appointed to make the decision. The only point left open for controversy is, whether such decision, when made, is conclusive and binding upon the states, and the people of the states. The reasons, why it should be so deemed, will now be submitted.

§ 377. In the first place, the judicial power of the United States rightfully extending to all such cases, its judgment becomes ipso facto conclusive between the parties before it, in respect to the points decided, unless some mode be pointed out by the constitution, in which that judgment may be revised. No such mode is pointed out. Congress is vested with ample authority to provide for the exercise by the Supreme Court of appellate jurisdiction from the decisions of all inferior tribunals, whether state or national, in cases within the purview of the judicial power of the United States; but no mode is provided, by which any superior tribunal can re-examine, what the Supreme Court has itself decided. Ours is emphatically a government of laws, and not of men; and judicial decisions of the highest tribunal, by the known course of the common law, are considered, as establishing the true construction of the laws, which are brought into controversy before it. The case is not alone considered as decided and settled; but the principles of the decision are held, as precedents and authority, to bind future cases of the same nature. This is the constant practice under our whole system of jurisprudence. Our ancestors brought it with them, when they first emigrated to this country; and it is, and always has been considered, as the great security of our rights, our liberties, and our property. It is on this account, that our law is justly deemed certain, and founded in permanent principles, and not dependent upon the caprice, or will of particular judges. A more alarming doctrine could not be promulgated by any American court, than that it was at liberty to disregard all former rules and decisions, and to decide for itself, without reference to the settled course of antecedent principles.

§ 378. This known course of proceeding, this settled habit of thinking, this conclusive effect of judicial adjudications, was in the full view of the framers of the constitution. It was required, and enforced in every state in the Union; and a departure from it would have been justly deemed an approach to tyranny and arbitrary power, to the exercise of mete discretion, and to the abandonment of all the just checks upon judicial authority. It would seem impossible, then, to presume, if the people intended to introduce a new rule in respect to the decisions of the Supreme Court, and to limit the nature and operations of their judgments in a manner wholly unknown to the common law, and to our existing jurisprudence, that some indication of that intention should not be apparent on the face of the constitution. We find, (Art. 4,) that the constitution has declared, that full faith and credit shall be given in each state to the judicial proceedings of every other state. But no like provision has been made in respect to the judgments of the courts of the United States, because they were plainly supposed to be of paramount and absolute obligation throughout all the states. If the judgments of the Supreme Court upon constitutional questions are conclusive and binding upon the citizens at large, must they not be equally conclusive upon the states? If the states are parties to that instrument, are not the people of the states also parties?

§ 379. It has been said, “that however true it may be, that the judicial department is, in all questions submitted to it by the forms of the constitution, to decide in the last resort, this resort must necessarily be deemed the last in relation to the other departments of the government, not in relation to the rights of the parties to the constitutional compact, from which the judicial, as well as the other departments hold their delegated trusts. On any other hypothesis, the delegation of judicial power would annul the authority delegating it; and the concurrence of this department with the others in usurped powers might subvert for ever, and beyond the possible reach of any rightful remedy, the very constitution, which all were instituted to preserve.”10 Now, it is certainly possible, that all the departments of a government may conspire to subvert the constitution of that government, by which they are created. But if they should so conspire, there would still remain an adequate remedy to redress the evil. In the first place, the people, by the exercise of the elective franchise, can easily check and remedy any dangerous, palpable, and deliberate infraction of the constitution in two of the great departments of government; and, in the third department, they can remove the judges, by impeachment, for any corrupt conspiracies. Besides these ordinary remedies, there is a still more extensive one, embodied in the form of the constitution, by the power of amending it, which is always in the power of three fourths of the states. It is a supposition not to be endured for a moment, that three fourths of the states would conspire in any deliberate, dangerous, and palpable breach of the constitution. And if the judicial department alone should attempt any usurpation, congress, in its legislative capacity, has full power to abrogate the injurious effects of such a decision. Practically speaking, therefore, there can be very little danger of any such usurpation or deliberate breach.

§ 380. But it is always a doubtful mode of reasoning to argue from the possible abuse of powers, that they do not exist.11 Let us look for a moment at the consequences, which flow from the doctrine on the other side. There are now twenty-four states in the Union, and each has, in its sovereign capacity, a right to decide for itself in the last resort, what is the true construction of the constitution; what are its powers; and what are the obligations founded on it. We may, then, have, in the free exercise of that right, twentyfour honest, but different expositions of every power in that constitution, and of every obligation involved in it. What one state may deny, another may assert; what one may assert at one time, it may deny at another time. This is not mere supposition. It has, in point of fact, taken place. There never has been a single constitutional question agitated, where different states, if they have expressed any opinion, have not expressed different opinions; and there have been, and, from the fluctuating nature of legislative bodies, it may be supposed? that there will continue to be, cases, in which the same state will at different times hold different opinions on the same question. Massachusetts at one time thought the embargo of 1807 unconstitutional; at another a majority, from the change of parties, was as decidedly the other way. Virginia, in 1810, thought that the Supreme Court was the common arbiter; in 1829 she thought differently.12 What, then, is to become of the constitution, if its powers are thus perpetually to be the subject of debate and controversy? What exposition is to be allowed to be of authority? Is the exposition of one state to be of authority there, and the reverse to be of authority in a neighbouring state, entertaining an opposite exposition? Then, there would be at no time in the United States the same constitution in operation over the whole people. Is a power, which is doubted, or denied by a single state, to be suspended either wholly, or in that state? Then, the constitution is practically gone, as a uniform system, or indeed, as any system at all, at the pleasure of any state. If the power to nullify the constitution exists in a single state, it may rightfully exercise it at its pleasure. Would not this be a far more dangerous and mischievous power, than a power granted by all the states to the judiciary to construe the constitution? Would not a tribunal, appointed under the authority of all, be more safe, than twenty-four tribunals acting at their own pleasure, and upon no common principles and cooperation? Suppose congress should declare war; shall one state have power to suspend it? Suppose congress should make peace; shall one state have power to involve the whole country in war? Suppose the president and senate should make a treaty; shall one state declare it a nullity, or subject the whole country to reprisals for refusing to obey it? Yet, if every state may for itself judge of its obligations under the constitution, it may disobey a particular law or treaty, because it may deem it an unconstitutional exercise of power, although every other state shall concur in a contrary opinion. Suppose congress should lay a tax upon imports burthensome to a particular state, or for purposes, which such state deems unconstitutional, and yet all the other states are in its favour; is the law laying the tax to become a nullity? That would be to allow one state to withdraw a power from the Union, which was given by the people of all the states. That would be to make the general government the servant of twenty-four masters, of different wills and different purposes, and yet bound to obey them all.13

§ 381. The argument, therefore, arising from a possibility of an abuse of power, is, to say the least of it, quite as strong the other way. The constitution is in quite as perilous a state from the power of overthrowing it lodged in every state in the Union, as it can be by being lodged in any department of the federal government. There is this difference, however, in the cases, that if there be federal usurpation, it may be checked by the people of all the states in a constitutional way. If there be usurpation by a single state, it is, upon the theory we are considering, irremediable. Other difficulties, however, attend the reasoning we are considering. When it is said, that the decision of the Supreme Court in the last resort is obligatory, and final “in relation to the authorities of the other departments of the government,” is it meant of the federal government only, or of the states also? If of the former only, then the constitution is no longer the supreme law of the land, although all the state functionaries are bound by ah oath to support it. If of the latter also, then it is obligatory upon the state legislatures, executives, and judiciaries. It binds them; and yet it does not bind the people of the states, or the states in their sovereign capacity. The states may maintain one construction of it, and the functionaries of the state are bound by another. If, on the other hand, the state functionaries are to follow the construction of the state, in opposition to the construction of the Supreme Court, then the constitution, as actually administered by the different functionaries, is different; and the duties required of them may be opposite, and in collision with each other. If such a state of things is the just result of the reasoning, may it not justly be suspected, that the reasoning itself is unsound?

§ 382. Again; it is a part of this argument, that the judicial interpretation is not binding “in relation to the rights of the parties to the constitutional compact.” “On any other hypothesis the delegation of judicial power would annul the authority delegating it.” Who then are the parties to this contract? Who did delegate the judicial power? Let the instrument answer for itself. The people of the United States are the parties to the constitution. The people of the United States delegated the judicial rower. It was not a delegation by the people of one state, but by the people of all the states. Why then is not a judicial decision binding in each state, until all, who delegated the power, in some constitutional manner concur in annulling or overruling the decision? Where shall we find the clause, which gives the power to each state to construe the constitution for all; and thus of itself to supersede in its own favour the construction of all the rest? Would not this be justly deemed a delegation of judicial power, which would annul the authority delegating it?14 Since the whole people of the United States have concurred in establishing the constitution, it would seem most consonant with reason to presume, in the absence of all contrary stipulations, that they did not mean, that its obligatory force should depend upon the dictate or opinion of any single state. Even under the confederation, (as has been already stated,) it was unanimously resolved by congress, that “as state legislatures are not competent to the making of such compacts or treaties, [with foreign states,] so neither are they competent in that capacity authoritatively to decide on, or ascertain the construction and sense of them.” And the reasoning, by which this opinion is supported, seems absolutely unanswerable.15

If this was true under such an instrument, and that construction was avowed before the whole American people, and brought home to the knowledge of the state legislatures, how can we avoid the inference, that under the constitution, where an express judicial power in cases arising under the constitution was provided for, the people must have understood and intended, that the states should have no right to question, or control such judicial interpretation?

§ 383. In the next place, as the judicial power extends to all cases arising under the constitution, and that constitution is declared to be the supreme law, that supremacy would naturally he construed to extend, not only over the citizens, but over the states.16 This, however, is not left to implication, for it is declared to be the supreme law of the land, “any thing in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.” The people of any state cannot, then, by any alteration of their state constitution, destroy, or impair that supremacy. How, then, can they do it in any other less direct manner? Now, it is the proper function of the judicial department to interpret laws, and by the very terms of the constitution to interpret the supreme law. Its interpretation, then, becomes obligatory and conclusive upon all the departments of the federal government, and upon the whole people, so far as their rights and duties are derived from, or affected by that constitution. If then all the departments of the national government may rightfully exercise all the powers, which the judicial department has, by its interpretation, declared to be granted by the constitution; and are prohibited from exercising those, which are thus declared not to be granted by it, would it not be a solecism to hold, notwithstanding, that such rightful exercise should not be deemed the supreme law of the land, and such prohibited powers should still be deemed granted? It would seem repugnant to the first notions of justice, that in respect to the same instrument of government, different powers, and duties, and obligations should arise, and different rules should prevail, at the same time among the governed, from a right of interpreting the same words (manifestly used in one sense only) in different, nay, in opposite senses. If there ever was a case, in which uniformity of interpretation might well be deemed a necessary postulate, it would seem to be that of a fundamental law of a government. It might otherwise follow, that the same individual, as a magistrate, might be bound by one rule, and in his private capacity by another, at the very same moment.

§ 384. There would be neither wisdom nor policy in such a doctrine; and it would deliver over the constitution to interminable doubts, founded upon the fluctuating opinions and characters of those, who should, from time to time, be called to administer it. Such a constitution could, in no just sense, be deemed a law, much less a supreme or fundamental law. It would have none of the certainty or universality, which are the proper attributes of such a sovereign rule. It would entail upon us all the miserable servitude, which has been deprecated, as the result of vague and uncertain jurisprudence. Misera est servitus, ubi jus est vagum aut incertum. It would subject us to constant dissensions, and perhaps to civil broils, from the perpetually recurring conflicts upon constitutional questions. On the other hand, the worst, that could happen from a wrong decision of the judicial department, would be, that it might require the interposition of congress, or, in the last resort, of the amendatory power of the states, to redress the grievance.

§ 385. We find the power to construe the constitution expressly confided to the judicial department, without any limitation or qualification, as to its conclusiveness. Who, then, is at liberty, by general implications, not from the terms of the instrument, but from mere theory, and assumed reservations of sovereign right, to insert such a limitation or qualification? We find, that to produce uniformity of interpretation, and to preserve the constitution, as a perpetual bond of union, a supreme arbiter or authority of construing is, if not absolutely indispensable, at least, of the highest possible practical utility and importance. Who, then, is at liberty to reason down the terms of the constitution, so as to exclude their natural force and operation?

§ 386. We find, that it is the known course of the judicial department of the several states to decide in the last resort upon all constitutional questions arising in judgment; and that this has always been maintained as a rightful exercise of authority, and conclusive upon the whole state.17 As such, it has been constantly approved by the people, and never withdrawn from the courts by any amendment of their constitutions, when the people have been called to revise them. We find, that the people of the several states have constantly relied upon this last judicial appeal, as the bulwark of their state rights and liberties; and that it is in perfect consonance with the whole structure of the jurisprudence of the common law. Under such circumstances, is it not most natural to presume, that the same rule was intended to be applied to the constitution of the United States? And when we find, that the judicial department of the United States is actually entrusted with a like power, is it not an irresistible presumption, that it had the same object, and was to have the same universally conclusive effect? Even under the confederation, an instrument framed with infinitely more jealousy and deference for state rights, the judgments of the judicial department appointed to decide controversies between states was declared to be final and conclusive; and the appellate power in other cases was held to overrule all state decisions and state legislation.18

§ 387. If, then, reasoning from the terms of the constitution, and the known principles of our jurisprudence, the appropriate conclusion is, that the judicial department of the United States is, in the last resort, the final expositor of the constitution, as to all questions of a judicial nature; let us see, in the next place, how far this reasoning acquires confirmation from the past history of the constitution, and the practice under it.

§ 388. That this view of the constitution was taken by its framers and friends, and was submitted to the people before its adoption, is positively certain. The Federalist 19 says, “Under the national government, treaties and articles of treaties as well as the law of nations, will always be expounded in one sense, and executed in the same manner; whereas, adjudications on the same points and questions in thirteen states, or three or four confederacies, will not always accord, or be consistent; and that as well from the variety of independent courts and judges appointed by different and independent governments, as from the different local laws, which may affect and influence them. The wisdom of the convention in committing such questions to the jurisdiction and judgment of courts appointed by, and responsible only to, one national government, cannot be too much commended.” Again, referring to the objection taken, that the government was national, and not a confederacy of sovereign states, and after stating, that the jurisdiction of the national government extended to certain enumerated objects only, and left the residue to the several states, it proceeds to say:20 “It is true, that in controversies between the two jurisdictions (state and national) the tribunal, which is ultimately to decide, is to be established under the general government. But this does not change the principle of the case. The decision is to be impartially made according to the rules of the constitution, and all the usual and most effectual precautions are taken to secure this impartiality. Some such tribunal is clearly essential to prevent an appeal to the sword, and a dissolution of the compact. And that it ought to be established under the general, rather than under the local governments, or, to speak more properly, that it could be safely established under the first alone, is a position not likely to be combated.”21

§ 389. The subject is still more elaborately considered in another number,22 which treats of the judicial department in relation to the extent of its powers. It is there said, that there ought always to be a constitutional method of giving efficacy to constitutional provisions; that if there are such things as political axioms, the propriety of the judicial department of a government being coextensive with its legislature, may be ranked among the number;23 that the mere necessity of uniformity in the interpretation of the national law decides the question; that thirteen independent courts of final jurisdiction over the same causes is a hydra of government, from which nothing but contradiction and confusion can proceed; that controversies between the nation and its members can only, be properly referred to the national tribunal; that the peace of the whole ought not to be left at the disposal of a part; and that whatever practices may have a tendency to disturb the harmony of the states, are proper objects of federal superintendence and control.24

§ 390. The same doctrine was constantly avowed in the state conventions, called to ratify the constitution. With some persons it formed a strong objection to the constitution; with others it was deemed vital to its existence and value.25 So, that it is indisputable, that the constitution was adopted under a full knowledge of this exposition of its grant of power to the judicial department.26

§ 391. This is not all. The constitution has now been in full operation more than forty years; and during this period the Supreme Court has constantly exercised this power of final interpretation in relation, not only to the constitution, and laws of the Union, but in relation to state acts and state constitutions and laws, so far as they affected the constitution, and laws, and treaties of the United States.27 Their decisions upon these grave questions have never been repudiated, or impaired by congress.28 No state has ever deliberately or forcibly resisted the execution of the judgments founded upon them; and the highest state tribunals have, with scarcely a single exception, acquiesced in, and, in most instances, assisted in executing them.29 During the same period, eleven states have been admitted into the Union, under a full persuasion, that the same power would be exerted over them. Many of the states have, at different times within the same period, been called upon to consider, and examine the grounds, on which the doctrine has been maintained, at the solicitation of other states which felt, that it operated injuriously, or might operate injuriously upon their interests. A great majority of the states, which have been thus called upon in their legislative capacities to express opinions, have maintained the correctness of the doctrine, and the beneficial effects of the powers, as a bond of union, in terms of the most unequivocal nature.30 Whenever any amendment has been proposed to change the tribunal, and substitute another common umpire or interpreter, it has rarely received the concurrence of more than two or three states, and has been uniformly rejected by a great majority, either silently, or by an express dissent. And instances have occurred, in which the legislature of the same state has, at different times, avowed opposite opinions, approving at one time, what it had denied, or at least questioned at another. So, that it may be asserted with entire confidence, that for forty years three fourths of all the states composing the Union have expressly assented to, or silently approved, this construction of the constitution, and have resisted every effort to restrict, or alter it. A weight of public opinion among the people for such a period, uniformly thrown into one scale so strongly, and so decisively, in the midst of all the extraordinary changes of parties, the events of peace and of war, and the trying conflicts of public policy and state interests, is perhaps unexampled in the history of all other free governments.31 It affords, as satisfactory a testimony in favour of the just and safe operation of the system, as can well be imagined; and, as a commentary upon the constitution itself, it is as absolutely conclusive, as any ever can be, and affords the only escape from the occurrence of civil conflicts, and the delivery over of the subject to interminable disputes.32

§ 392. In this review of the power of the judicial department, upon a question of its supremacy in the interpretation of the constitution, it has not been thought necessary to rely on the deliberate judgments of that department in affirmance of it. But it may be proper to add that the judicial department has not only constantly exercised this right of interpretation in the last resort; but its whole course of reasonings and operation has proceeded upon the ground, that, once made, the interpretation was conclusive, as well upon the states, as the people.33

§ 393. But it may be asked, as it has been asked, what is to be the remedy, if there be any misconstruction of the constitution on the part of the government of the United States, or its functionaries, and any powers exercised by them, not warranted by its true meaning? To this question a general answer may be given in the words of its early expositors: “The same, as if the state legislatures should violate their respective constitutional authorities.” In the first instance, if this should be by congress, “the success of the usurpation will depend on the executive and judiciary departments, which are to expound, and give effect to the legislative acts; and, in the last resort, a remedy must be obtained from the people, who can, by the election of more faithful representatives, annul the acts of the usurpers. The truth is, that this ultimate redress may be more confided in against unconstitutional acts of the federal, than of the state legislatures, for this plain reason, that, as every act of the former will be an invasion of the rights of the latter, these will ever be ready to mark the innovation, to sound the alarm to the people, and to exert their local influence in effecting a change of federal representatives. There being no such intermediate body between the state legislatures and the people, interested in watching the conduct of the former, violations of the state constitution are more likely to remain unnoticed and unredressed.”34

§ 394. In the next place, if the usurpation should be by the president, an adequate check may be generally found, not only in the elective franchise, but also in the controlling power of congress, in its legislative or impeaching capacity, and in an appeal to the judicial department. In the next place, if the usurpation should be by the judiciary, and arise from corrupt motives, the power of impeachment would remove the offenders; and in most other cases the legislative and executive authorities could interpose an efficient barrier. A declaratory or prohibitory law would, in many cases, be a complete remedy. We have, also, so far at least as a conscientious sense of the obligations of duty, sanctioned by an oath of office, and an indissoluble responsibility to the people for the exercise and abuse of power, on the part of different departments of the government, can influence human minds, some additional guards against known and deliberate usurpations; for both are provided for in the constitution itself. “The wisdom and the discretion of congress, (it has been justly observed,) their identity with the people, and the influence, which their constituents possess at elections, are, in this, as in many other instances, as, for example, that of declaring, war; the sole restraints; on this they have relied, to secure them from abuse. They are the restraints, on which the people must often solely rely in all representative governments.”35

§ 395. But in the next place, (and it is that, which would furnish a case of most difficulty and danger, though it may fairly be presumed to be of rare occurrence,) if the legislature, executive, and judicial departments should all concur in a gross usurpation, there is still a peaceable remedy provided by the constitution. It is by the power of amendment, which may always be applied at the will of three fourths of the states. If, therefore, there should be a corrupt cooperation of three fourths of the states for permanent usurpation, (a case not to be supposed, or if supposed, it differs not at all in principle or redress from the case of a majority of a state or nation having the same intent,) the case is certainly irremediable under any known forms of the constitution. The states may now by a constitutional amendment, with few limitations, change the whole structure and powers of the government, and thus legalize any present excess of power. And the general right of a society in other cases to change the government at the will of a majority of the whole people, in any manner, that may suit its pleasure, is undisputed, and seems indisputable. If there be any remedy at all for the minority in such cases, it is a remedy never provided for by human institutions. It is by a resort to the ultimate right of all human beings in extreme cases to resist oppression, and to apply force against ruinous injustice.36

§ 396. As a fit conclusion to this part of these commentaries, we cannot do better than to refer to a confirmatory view, which has been recently presented to the public by one of the framers of the constitution, who is now, it is believed, the only surviving member of the federal convention, and who, by his early as well as his later labours, has entitled himself to the gratitude of his country, as one of its truest patriots, and most enlightened friends. Venerable, as he now is, from age and character, and absolved from all those political connexions, which may influence the judgment, and mislead the mind, he speaks from his retirement in a voice, which cannot be disregarded, when it instructs us by its profound reasoning, or admonishes us of our dangers by its searching appeals. However particular passages may seem open to criticism, the general structure of the argument stands on immovable foundations, and can scarcely perish, but with the constitution, which it seeks to uphold.37

Footnotes:

1. The point was very strongly argued, and much considered, in the case of Cohens v. Virginia, in the Supreme Court in 1821, (6 Wheat. R. 264.) The whole argument, as well as the judgment, deserves an attentive reading. The result, to which the argument against the existence of a common arbiter leads, is presented in a very forcible manner by Mr. Chief Justice Marshall, in pages 376, 377.

“The questions presented to the court by the two first points made at the bar are of great magnitude, and may be truly said vitally to affect the Union. They exclude the inquiry, whether the constitution and laws of the United States have been violated by the judgment, which the plaintiffs in error seek to review; and maintain, that, admitting such violation, it is not in the power of the government to apply a corrective. They maintain, that the nation does not possess a department capable of restraining peaceably, and by authority of law, any attempts, which maybe made by a part against the legitimate powers of the whole; and that the government is reduced to the alternative of submitting to such attempts, or of resisting them by force. They maintain, that the constitution of the United States has provided no tribunal for the final construction of itself, or of the laws or treaties of the nation; but that this power may be exercised in the last resort by the courts of every state in the Union. That the constitution, laws, and treaties, may receive as many constructions, as there are states; and that this is not a mischief, or, if a mischief, is irremediable. These abstract propositions are to be determined; for he, who demands decision without permitting inquiry, affirms, that the decision he asks does not depend on inquiry.

“If such be the constitution, it is the duty of this court to bow with respectful submission to its provisions. If such be not the constitution, it is equally the duty of this court to say so; and to perform that task, which the American people have assigned to the judicial department.”

2. See the Federalist, No. 33.

3. Mr. Jefferson carries his doctrine much farther, and holds, that each department of government has an exclusive right, independent of the judiciary, to decide for itself, as to the true construction of the constitution. ” My construction,” says he, ” is very different from that, you quote. It is, that each department of the government is truly independent of the others, and has an equal right to decide for itself, what is the meaning of the constitution in the laws submitted to its action, and especially, when it is to act ultimately and without appeal.” And he proceeds to give examples, in which he disregarded, when president, the decisions of the judiciary, and refers to the alien and sedition laws, and the case of Marbury v. Madison, (1 Cranch, 137.) 4 Jefferson’s Corresp. 316, 317. See also 4 Jefferson’s Corresp. 27; Id. 75; Id. 372, 374.

4. See 4 Elliot’s Debates, 315 to 320.

5. The Federalist, No. 44. — Mr. Madison, in the Virginia Report of Jan. 1800, has gone into a consideration of this point, and very properly suggested, that there may be infractions of the constitution not within the reach of the judicial power, or capable of remedial redress through the instrumentality of courts of law. But we cannot agree with him, that in such cases, each state may take the construction of the constitution into its own hands, and decide for itself in the last resort; much less, that in a case of judicial cognizance, the decision is not binding on the states. See Report p. 6, 7, 8, 9.

6. Dane’s App. §44, 45, p. 52 to 59. — It affords me very sincere gratification to quote the following passage from the learned Commentaries of Mr. Chancellor Kent, than whom very few judges in our country are more profoundly versed in constitutional law. After enumerating the judicial powers in the constitution, he proceeds to observe: “The propriety and fitness of these judicial powers seem to result, as a necessary consequence, from the union of these states in one national government, and they may be considered as requisite to its existence. The judicial power in every government must be co-extensive with the power of legislation. Were there no power to interpret, pronounce, and execute the law, the government would either perish through its own imbecility, as was the case with the old confederation, or other powers must be assumed by the legislative body to the destruction of liberty.” 1 Kent’s Comm. (2d ed. p. 296,) Lect. 14, 277.

7. 4 Dane’s Abridg. ch. 187. art. 20, §15, p. 590; Dane’s App. §42, p. 49, 50; §44, p. 52, 53; 1 Wilson’s Lectures, 461, 462, 463.

8. See Address of Congress, Feb. 1787; Journals of Congress, p. 33; Rawle on the Constitution, App. 2, p. 316.

9. Bacon’s Abridgment, Statute. H.

10. Madison’s Virginia Report, Jan. 1800, p. 8, 9.

11. See Anderson v. Dunn, 6 Wheaton’s R. 204, 232.

12. Dane’s App. §44, 45, p. 52 to 59, §54, p. 66; 4 Elliot’s Debates, 338, 339.

13. Webster’s Speeches, 420; 4 Elliots Debates, 339.

14. There is vast force in the reasoning Mr. Webster on this subject, in his great Speech on Mr. Foot’s Resolutions in the senate, in 1830, which well deserves the attention of every statesman and jurist. See 4 Elliot’s Debates, 338, 339, 343, 344, and Webster’s Speeches, p. 407, 408, 418, 419, 420; Id. 430, 431, 432.

15. Journals of Congress, April 13, 1787, p. 32, etc. Rawle on the Constitution, App. 2, p. 316, etc.

16. The Federalist, No. 33.

17. 2 Elliot’s Debates, 248, 328, 329, 395; Grimke’s Speech in 1828, p. 25, etc.; Dane’s App. § 44, 45, p. 52 to 59; Id. § 48, p. 62.

18. Dane’s App. §52, p. 65; Penhallow v. Doane, 3 Dall. 54; Journals of Congress, 1779, Vol. 5, p. 86 to 90; 4 Cranch, 2.

19. The Federalist, No. 3.

20. The Federalist, No. 39.

21. See also The Federalist, No. 33.

22. The Federalist, No. 80.

23. The same remarks will be found pressed with great force by Mr. Chief Justice Marshall, in delivering the opinion of the court in Cohens v. Virginia, (6 Wheat. 264, 384.)

24. In The Federalist, No. 78 and 82, the same course of reasoning is pursued, and the final nature of the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court is largely insisted on. In the Convention of Connecticut, Mr. Ellsworth (afterwards Chief Justice of the United States) used the following language: “This constitution defines the extent of the powers of the general government. If the general legislature should at any time overleap their limits, the judicial department is the constitutional check. If the United States go beyond their powers; if they make a law, which the constitution does not authorize, it is void; and the judicial power, the national judges, who, to secure their impartiality, are to be made independent, will declare it void. On the other hand, if the states go beyond their limits; if they make a law, which is a usurpation upon the general government, the law is void, and upright and independent judges will declare it. Still, however, if the United States and the individual states will quarrel; if they want to fight, they may do it, and no frame of government can possibly prevent it.” In the debates in the South Carolina legislature, when the subject of calling a convention to ratify or reject the constitution was before them,* Mr. Charles Pinckney (one of the members of the convention) avowed the doctrine in the strongest terms. “That a supreme federal jurisdiction was indispensable,” said he, “cannot be denied. It is equally true, that in order to ensure the administration of justice, it was necessary to give all the powers, original as well as appellate, the constitution has enumerated. Without it we could not expect a due observance of treaties; that the state judiciaries would confine themselves within their proper sphere; or that a general sense of justice would pervade the Union, etc. That to ensure these, extensive authorities were necessary; particularly so, were they in a tribunal, constituted as this is, whose duty it would be, not only to decide all national questions, which should arise within the Union; but to control and keep the state judiciaries within their proper limits, whenever they should attempt to interfere with the power.”

* Debates in 1788, printed by A. E. Miller, 1831, Charleston, p. 7.

25. It would occupy too much space to quote the passages at large. Take for an instance, in the Virginia debates, Mr. Madison’s remarks. ” It may be a misfortune, that in organizing any government, the explication of its authority should be left to any of its co-ordinate branches. There is no example in any country, where it is otherwise. There is no new policy in submitting it to the judiciary of the United States.” 2 Elliot’s Debates, 390. See also Id. 380, 383, 395, 400, 404, 418. See also North Carolina Debates, 3 Elliot’s Debates, 125, 127, 128, 130, 133, 134, 139, 141, 142, 143; Pennsylvania Debates, 3 Elliot’s Debates, 280, 313. Mr. Luther Martin, in his letter to the Maryland Convention, said: ” By the third article the judicial power is vested in one Supreme Court, etc. These courts, and these only, will have a right to decide upon the laws of the United States, and all questions arising upon their construction, etc. Whether, therefore, any laws, etc. of congress, or acts of its president, etc. are contrary to, or warranted by the constitution, rests only with the judges, who are appointed by congress to determine; by whose determinations every state is bound.” 3 Elliot’s Debates, 44, 45; Yates’s Minutes, etc. See also The Federalist, No. 78.

26. See Mr. Pinckney’s Observations cited in Grimke’s Speech in 1828, p. 86, 87.

27. Dane’s App. §44, p. 53, 54, 55; Grimke’s Speech, 1828, p. 34 to 42.

28. In the debate in the first congress organized under the constitution, the same doctrine was openly avowed, as indeed it has constantly been by the majority of congress at all subsequent periods. See 1 Lloyd’s Debates, 219 to 599; 2 Lloyd’s Debates, 284 to 327.

29. Chief Justice M’Kean, in Commonwealth v.Cobbett (3 Dall. 473,) seems to have adopted a modified doctrine, and to have held, that the Supreme Court was not the common arbiter; but if not, the only remedy was, not by a state deciding for itself, as in case of a treaty between independent governments, but by a constitutional amendment by the states. But see, on the other hand, the opinion of Chief Justice Spencer, in Andrews v. Montgomery, 19 Johns. R. 164.

30. Massachusetts, in her Resolve of February 12, 1799, (p. 57,) in answer to the Resolutions of Virginia of 1798, declared, ” that the decision of all cases in law and equity, arising under the constitution of the United States, and the construction of all laws made in pursuance thereof, are exclusively vested by the people in the judicial courts of the United States;” and ” that the people in that solemn compact, which is declared to be the supreme law of the land, have not constituted the state legislatures the judges of the acts or measures of the federal government, but have confided to them the power of proposing such amendments” etc.; and “that by this construction of the constitution, an amicable and dispassionate remedy is pointed out for any evil, which experience may prove to exist, and the peace and prosperity of the United States may be preserved without interruption.” See also Dane’s App. §44, p. 56; Id. 80. Mr. Webster’s Speech in the Senate, in 1830, contains an admirable exposition of the same doctrines. Webster’s Speeches, 410, 419, 420, 421. In June, 1821. the House of Representatives of NewHampshire passed certain resolutions. (172 yeas to 9 nays,) drawn up (as is understood) by one of her most distinguished statesmen, asserting the same doctrines. Delaware, in January, 1831, and Connecticut and Massachusetts held the same, in May, 1831.

31. Virginia and Kentucky denied the power in 1793 and 1800; Massachusetts, Delaware, Rhode-Island, New-York, Connecticut, NewHampshire, and Vermont disapproved of the Virginia resolutions, and passed counter resolutions. (North American Review, October, 1830, p. 500.) No other state appears to have approved the Virginia resolutions. (Ibid.) In 1810 Pennsylvania proposed the appointment of another tribunal than the Supreme Court to determine disputes between the general and state governments. Virginia, on that occasion, affirmed, that the Supreme Court was the proper tribunal; and in that opinion New-Hampshire, Vermont, North-Carolina, Maryland, Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, and New-Jersey concurred; and no one state approved of the amendment (North American Review, October, 1830, p. 507 to 512; Dane’s App. §55, p. 67; 6 Wheat. R. 358, note.) Recently, in March, 1831, Pennsylvania has resolved, that the 25th section of the judiciary act of 1789, ch. 20, which gives the Supreme Court appellate jurisdiction from state courts on constitutional questions, is authorized by the constitution, and sanctioned by experience, and also all other laws empowering the federal judiciary to maintain the supreme laws.

32. Upon this subject the speech of Mr. Webster in the Senate, in 1830, presents the whole argument in a very condensed and powerful form. The following passage is selected, as peculiarly appropriate:

“The people, then, sir, erected this government. They gave it a constitution, and in that constitution they have enumerated the powers which they bestow on it. They have made it a limited government. They have defined its authority. They have restrained it to the exercise of such powers, as are granted; and all others, they declare, are reserved to the states, or the people. But, sir, they have not stopped here. If they had, they would have accomplished but half their work. No definition can be so clear, as to avoid possibility of doubt; no limitation so precise, as to exclude all uncertainty. Who, then, shall construe this grant of the people? Who shall interpret their will, where it may be supposed they have left it doubtful? With whom do they repose this ultimate right of deciding on the powers of the government? Sir, they have settled all this in the fullest manner. They have left it, with the government itself, in its appropriate branches. Sir, the very chief end, the main design, for which the whole constitution was framed and adopted, was to establish a government, that should not be obliged to act through state agency, or depend on state opinion and state discretion. The people had had quite enough of that kind of government, under the confederacy. Under that system, the legal action – the application of law to individuals, belonged exclusively to the states. Congress could only recommend – their acts were not of binding force, till the states had adopted and sanctioned them. Are we in that condition still? Are we yet at the mercy of state discretion, and state construction? Sir, if we are, then vain will be our attempt to maintain the constitution, under which we sit.

“But, sir, the people have wisely provided, in the constitution itself, a proper, suitable mode and tribunal for settling questions of constitutional law. There are, in the constitution, grants of powers to Congress; and restrictions on these powers. There are, also, prohibitions on the states. Some authority must, therefore, necessarily exist, having the ultimate jurisdiction to fix and ascertain the interpretation of these grants, restrictions, and prohibitions. The constitution has itself pointed out, ordained, and established that authority. How has it accomplished this great and essential end? By declaring, sir, that ‘ the constitution and the law of the United States, made in pursuance thereof, shall be the supreme law of the land, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.’

“This, sir, was the first great step. By this, the supremacy of the constitution and laws of the United States is declared. The people so will it. No state law is to be valid, which comes in conflict with the constitution, or any law of the United States passed in pursuance of it. But who shall decide this question of interference? To whom lies the last appeal? This, sir, the constitution itself decides, also, by declaring, ‘that the judicial power shall extend to all cases arising under the constitution and laws of the United States.’ These two provisions, sir, cover the whole ground. They are, in truth, the keystone of the arch. With these, it is a constitution; without them, it is a confederacy. In pursuance of these clear and express provisions, congress established, at its very first session, in the judicial act, a mode for carrying them into full effect, and for bringing all questions of constitutional power to the final decision of the Supreme Court. It then, sir, became a government. It then had the means of self-protection; and, but for this, it would, in all probability, have been now among things, which are past. Having constituted the government, and declared its powers, the people have further said, that since somebody must decide on the extent of these powers, the government shall itself decide; subject, always, like other popular governments, to its responsibility to the people. And now, sir, I repeat, how is it, that a state legislature acquires any power to interfere? Who, or what, gives them the right to say to the people, ‘ We, who are your agents and servants for one purpose, will undertake to decide, that your other agents and servants, appointed by you for another purpose, have transcended the authority you gave them!’ The reply would be, I think, not impertinent -‘ Who made you a judge over another’s servants? To their own masters they stand or fall.’

“Sir, I deny this power of state legislatures altogether. It cannot stand the test of examination. Gentlemen may say, that in an extreme case, a state government might protect the people from intolerable oppression. Sir, in such a case, the people might protect themselves, without the aid of the state governments. Such a case warrants revolution. It must make, when it comes, a law for itself. A nullifying act of a state legislature cannot alter the case, nor make resistance any more lawful. In maintaining these sentiments, sir, I am but asserting the rights of the people. I state what they have declared, and insist on their right to declare it. They have chosen to repose this power in the general government, and I think it my duty to support it, like other constitutional powers.”

See also 1 Wilson’s Law Lectures, 461, 462. – It is truly surprising, that Mr. Vice-President Calhoun, in his Letter of the 28th of August, 1832, to governor Hamilton, (published while the present work was passing through the press,) should have thought, that a proposition merely offered in the convention, and referred to a committee for their consideration, that ” the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court shall be extended to all controversies between the United States and an individual state, or the United States and the citizens of an individual state,”* should, in connexion with others giving a negative on state laws, establish the conclusion, that the convention, which framed the constitution, was opposed to granting the power to the general government, in any form, to exercise any control whatever over a state by force, veto, or judicial process, or in any other form. This clause for conferring jurisdiction on the Supreme Court in controversies between the United States and the states, must, like the other controversies between states, or between individuals, referred to the judicial power, have been intended to apply exclusively to suits of a civil nature, respecting property, debts contracts, or other claims by the United States against a state; and not to the decision of constitutional questions in the abstract. At a subsequent period of the convention, the judicial power was expressly extended to all cases arising under the constitution, laws, and treaties, of the United States, and to all controversies, to which the United States should be a party,** thus covering the whole ground of a right to decide constitutional questions of a judicial nature. And this, as the Federalist informs us, was the substitute for a negative upon state laws, and the only one, which was deemed safe or efficient. The Federalist No. 80.

* Journal of Convention, 20th Aug. p. 235.

** Journal of Convention, 27th Aug. p. 298.

33. Martin v. Hunter, I Wheat. R. 304, 334, etc. 342 to 348; Cohens v. The State of Virginia,6 Wheat. R. 264, 376, 377 to 392; Id. 413 to 432; Bank of Hamilton v. Dudley, 2 Peters’s R. 524; Ware v. Hylton, 3 Dall. 199; I Cond. R. 99, 112. The language of Mr. Chief Justice Marshall, in delivering the opinion of the court in Cohens v. Virginia, presents the argument in favour of the jurisdiction of the judicial department in a very forcible manner.

“While weighing arguments drawn from the nature of government, and from the general spirit of an instrument, and urged for the purpose of narrowing the construction, which the words of that instrument seem to require, it is proper to place in the opposite scale those principles, drawn from the same sources, which go to sustain the words in their full operation and natural import. One of these, which has been pressed with great force by the counsel for the plaintiffs in error, is, that the judicial power of every well constituted government must be coextensive with the legislative, and must be capable of deciding every judicial question, which grows out of the constitution and laws.

“If any proposition may be considered as a political axiom, this, we think, may be so considered. In reasoning upon it, as an abstract question, there would, probably, exist no contrariety of opinion respecting it. Every argument, proving the necessity of the department, proves also the propriety of giving this extent to it. We do not mean to say, that the jurisdiction of the courts of the Union should be construed to be coextensive with the legislative, merely because it is fit, that it should be so; but we mean to say, that this fitness furnishes an argument in construing the constitution, which ought never to be overlooked, and which is most especially entitled to consideration, when we are inquiring, whether the words of the instrument, which purport to establish this principle, shall be contracted for the purpose of destroying it.

“The mischievous consequences of the construction, contended for on the part of Virginia, are also entitled to great consideration. It would prostrate, it has been said, the government and its laws at the feet of every state in the Union. And would not this be its effect? What power of the government could be executed by its own means, in any state disposed to resist its execution by a course of legislation? The laws must be executed by individuals acting within the several states. If these individuals may be exposed to penalties, and if the courts of the Union cannot correct the judgments, by which these penalties may be enforced, the course of the government may be, at any time, arrested by the will of one of its members. Each member will possess a veto on the will of the whole.

“The answer, which has been given to this argument, does not deny its truth, but insists, that confidence is reposed, and may be safely reposed, in the state institutions; and that, if they shall ever become so insane, or so wicked, as to seek the destruction of the government, they may accomplish their object by refusing to perform the functions assigned to them.

“We readily concur with the counsel for the defendant in the declaration, that the cases, which have been put, of direct legislative resistance for the purpose of oppose the acknowledged powers of the government, are extreme cases, and in the hope, that they will never occur; capacity of the government to protect itself and its laws in such cases, would contribute in no inconsiderable degree to their occurrence.

“Let it be admitted, that the cases, which have been put, are extreme and improbable, yet there are gradations of opposition to the laws, far short of those cases, which might have a baneful influence on the affairs of the nation. Different states may entertain different opinions on the true construction of the constitutional powers of congress. We know, that at one time, the assumption of the debts, contracted by the several states during the war of our revolution, was deemed unconstitutional by some of them. We know, too, that at other times, certain taxes, imposed by congress, have been pronounced unconstitutional. Other laws have been questioned partially, while they were supported by the great majority of the American people. We have no assurance, that we shall be less divided, than we have been. States may legislate in conformity to their opinions, and may enforce those opinions by penalties. It would be hazarding too much to assert, that the judicatures of the states will be exempt from the prejudices, by which the legislatures and people are influenced, and will constitute perfectly impartial tribunal. In many states the judges are dependent for office and for salary on the will of the legislature. The constitution of the United States furnishes no security against the universal adoption of this principle. When we observe the importance, which that constitution attaches to the independence of judges, we are the less inclined to suppose, that it can have intended to leave these constitutional questions to tribunals, where this independence may not exist, in all cases where a state shall prosecute an individual, who claims the protection of an act of congress. These prosecutions may take place, even without a legislative act. A person, making a seizure under an act of congress, may be indicted as a trespasser, if force has been employed, and of this a jury may judge. How extensive may be the mischief, if the first decisions in such cases should be final!

“These collisions may take place in times of no extraordinary commotion. But a constitution is framed for ages to come, and is designed to approach immortality, as nearly as human institutions can approach it. Its course cannot always be tranquil. It is exposed to storms and tempests, and its framers must be unwise statesmen indeed, if they have not provided it, as far as its nature will permit, with the means of self-preservation from the perils it may be destined to encounter. No government ought to be so defective in its organization, as not to contain within itself the means of securing the execution of its own laws against other dangers, than those which occur every day. Courts of justice are the means most usually employed; and it is reasonable to expect, that a government should repose on its own courts, rather than on others. There is certainly nothing in the circumstances, under which our constitution was formed; nothing in the history of the times, which would justify the opinion, that the confidence reposed in the states was so implicit, as to leave in them and their tribunals the power of resisting or defeating, in the form of law, the legitimate measures of the Union. The requisitions of congress, under the confederation, were as constitutionally obligatory, as the laws enacted by the present congress. That they were habitually disregarded, is a fact of universal notoriety. With the knowledge of this fact, and under its full pressure, a convention was assembled to change the system. Is it so improbable, that they should confer on the judicial department the power of construing the constitution and laws of the Union in every case, in the last resort, and of preserving them from all violation from every quarter, so far as judicial decisions can preserve them, that this improbability should essentially affect the construction of the new system? We are told, and we are truly told, that the great change, which is to give efficacy to the present system, is its ability to act on individuals directly, instead of acting through the instrumentality of state governments. But, ought not this ability, in reason and sound policy, to he applied directly to the protection of individuals employed in the execution of the laws, as well as to their coercion? Your laws reach the individual without the aid of any other power; why may they not protect him from punishment for performing his duty in executing them?

“The counsel for Virginia endeavour to obviate the force of these arguments by saying, that the dangers they suggest, if not imaginary, are inevitable; that the constitution can make no provision against them; and that, therefore, in construing that instrument, they ought to be excluded from our consideration. This state of things, they say, cannot arise, until there shall be a disposition so hostile to the present political system, as to produce a determination to destroy it; and, when that determination shall be produced, its effects will not be restrained by parchment stipulations. The fate of the constitution will not then depend on judicial decisions. But, should no appeal be made to force, the states can put an end to the government by refusing to act. They have only not to elect senators, and it expires without a struggle.

“It is very true, that, whenever hostility to the existing system shall become universal, it will be also irresistible. The people made the constitution, and the people can unmake it. It is the creature of their will, and lives only by their will. But this supreme and irresistible power to make, or to unmake, resides only in the whole body of the people; not in any subdivision of them. The attempt of any of the parts to exercise. it is usurpation, and ought to be repelled by those, to whom the people have delegated their power of repelling it.

“The acknowledged inability of the government, then, to sustain itself against the public will, and, by force or otherwise, to control the whole nation, is no sound argument in support of its constitutional inability to preserve itself against a section of the nation acting in opposition to the general will.

“It is true, that if all the states, or a majority of them, refuse to elect senators, the legislative powers of the Union will be suspended. But if any one state shall refuse to elect them, the senate will not, on that account, be the less capable of performing all its functions. The argument founded on this fact would seem rather to prove the subordination of the parts to the whole, than the complete independence of any one of them. The framers of the constitution were, indeed, unable to make any provisions, which should protect that instrument against a general combination of the states, or of the people, for its destruction; and, conscious of this inability, they have not made the attempt. But they were able to provide against the operation of measures adopted in any one state, whose tendency might be to arrest the execution of the laws, and this it was the part of true wisdom to attempt. We think they have attempted it.”

See also M’Culloch v. Maryland, (4 Wheat. 316, 405, 406.) See also the reasoning of Mr. Chief Justice Jay, in Chisholm v. Georgia,(2 Dall. 419, S. C. 2 Peters’s Cond. R. 635, 670 to 675.) Osborn v. Bank of the United States,( 9 Wheat. 738, 818, 819;) and Gibbons v. Ogden,(9 Wheat. 1, 210.)

34. The Federalist, No. 44; 1 Wilson’s Law Lectures, 461, 462; Dane’s App. §58, p. 68.

35. Gibbons v. Ogden, 9) Wheat. R. 1, 197. — See also, on the same subject, the observations of Mr. Justice Johnson in delivering the opinion of the court, in Anderson v. Dunn, 6 Wheat. R. 204, 226.

36. See Webster’s Speeches, p. 408, 409; 1 Black. Comm. 161, 162. See also 1 Tucker’s Black. Comm. App. 73 to 75.

37. Reference is here made to Mr. Madison’s Letter, dated August, 1830, to Mr. Edward Everett, published in the North American Review for October, 1830. The following extract is taken from p. 537, et seq.

“In order to understand the true character of the constitution of the United States, the error, not uncommon, must be avoided, of viewing it through the medium, either of a consolidated government, or of a confederated government, whilst it is neither the one, nor the other; but a mixture of both. And having, in no model, the similitudes and analogies applicable to other systems of government, it must, more than any other, be its own interpreter according to its text and the facts of the case.

“From these it will be seen, that the characteristic peculiarities of the constitution are, 1, the mode of its formation; 2, the division of the supreme powers of government between the states in their united capacity, and the states in their individual capacities.

“1. It was formed, not by the governments of the component states, as the federal government, for which it was substituted was formed. Nor was it formed by a majority of the people of the United States, as a single community, in the manner of a consolidated government.

“It was formed by the states, that is, by the people in each of the states, acting in their highest sovereign capacity; and formed consequently, by the same authority, which formed the state constitutions.

“Being thus derived from the same source as the constitutions of the states, it has, within each state, the same authority, as the constitution of the state; and is as much a constitution, in the strict sense of the term, within its prescribed sphere, as the constitutions of the states are, within their respective spheres: but with this obvious and essential difference, that being a compact among the states in their highest sovereign capacity, and constituting the people thereof one people for certain purposes, it cannot be altered, or annulled at the will of the states individually, as the constitution of a state may. be at its individual will.

“2. And that it divides the supreme powers of government, between the government of the United States, and the governments of the individual states; is stamped on the face of the instrument; the powers of war and of taxation, of commerce and of treaties, and other enumerated powers vested in the government of the United States, being of as high and sovereign a character, as any of the powers reserved to the state governments.

“Nor is the government of the United States, created by the constitution, less a government in the strict sense of the term, within the sphere of its powers, than the governments created by the constitutions of the states are, within their several spheres. It is, like them, organized into legislative, executive, and judiciary departments. It operates, like them, directly on persons and things. And, like them, it has at command a physical force for executing the powers committed to it. The concurrent operation in certain cases is one of the features marking the peculiarity of the system.

“Between these different constitutional governments, the one operating in all the states, the others operating separately in each, with the aggregate powers of government divided between them, it could not escape attention, that controversies would arise concerning the boundaries of jurisdiction; and that some provision ought to be made for such occurrences. A political system, that does not provide for a peaceable and authoritative termination of occurring controversies, would not be more than the shadow of a government; the object and end of a real government being, the substitution of law and order for uncertainty, confusion, and violence.

“That to have left a final decision, in such cases, to each of the states, then thirteen, and already twenty-four, could not fail to make the constitution and laws of the United States different in different states, was obvious; and not less obvious, that this diversity of independent decisions must altogether distract the government of the union, and speedily put an end to the union itself. A uniform authority of the laws, is in itself a vital principle. Some of the most important laws could not be partially executed. They must be executed in all the states, or they could be duly executed in none. An impost, or an excise, for example, if not in force in some states, would be defeated in others. It is well known, that this was among the lessons of experience, which had a primary influence in bringing about the existing constitution. A loss of its general authority would moreover revive the exasperating questions between the states holding ports for foreign commerce, and the adjoining states without them; to which are now added, all the inland states, necessarily carrying on their foreign commerce through other states.

“To have made the decisions under the authority of the individual states, coordinate, in all cases, with decisions under the authority of the United States, would unavoidably produce collisions incompatible with the peace of society, and with that regular and efficient administration, which is of the essence of free governments. Scenes could not be avoided, in which a ministerial officer of the United States, and the correspondent officer of an individual state, would have rencounters in executing conflicting decrees; the result of which would depend on the comparative force of the local posses attending them; and that, a casualty depending on the political opinions and party feelings in different states.

“To have referred every clashing decision, under the two authorities, for a final decision, to the states as parties to the constitution, would be attended with delays, with inconveniences, and with expenses, amounting to a prohibition of the expedient; not to mention its tendency to impair the salutary veneration for a system requiring such frequent inter positions, nor the delicate questions, which might present themselves as to the form of stating the appeal, and as to the quorum for deciding it.

“To have trusted to negotiation for adjusting disputes between the government of the United States and the state governments, as between independent and separate sovereignties, would have lost sight altogether of a constitution and government for the Union; and opened a direct road from a failure of that resort, to the ultima ratio between nations wholly independent of, and alien to each other. If the idea had its origin in the process of adjustment between separate branches of the same government, the analogy entirely fails. In the case of disputes between independent parts of the same government, neither part being able to consummate its will, nor the government to proceed without a concurrence of the parts, necessity brings about an accommodation. In disputes between a state government, and the government of the United States, the case is practically, as well as theoretically different; each party possessing all the departments of an organized government, legislative, executive, and judiciary; and having each a physical force to support its pretensions. Although the issue of negotiation might sometimes avoid this extremity, how often would it happen among so many states, that an unaccommodating spirit in some would render that resource unavailing? A contrary supposition would not accord with a knowledge of human nature, or the evidence of our own political history.

“The constitution, not relying on any of the preceding modifications, for its safe and successful operation, has expressly declared, on the one hand, 1, ‘that the constitution, and the laws made in pursuance thereof, and all treaties made under the authority of the United States shall be the supreme law of the land; 2, that the judges of every state shall be bound thereby, any thing in the constitution and laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding; 3, that the judicial power of the United States shall extend to all cases in law and equity arising under the constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made under their authority, etc.’

“On the other hand, as a security of the rights and powers of the states, in their individual capacities, against an undue preponderance of the powers granted to the government over them in their united capacity, the constitution has relied on, (1,) the responsibility of the senators and representatives in the legislature of the United States to the legislatures and people of the states; (2,) the responsibility of the president to the people of the United States; and ( 3,) the liability of the executive and judicial functionaries of the United States to impeachment by the representatives of the people of the states, in one branch of the legislature of the United States, and trial by the representatives of the states, in the other branch: the state functionaries, legislative, executive, and judicial, being, at the same time, in their appointment and responsibility, altogether independent of the agency or authority of the United States.